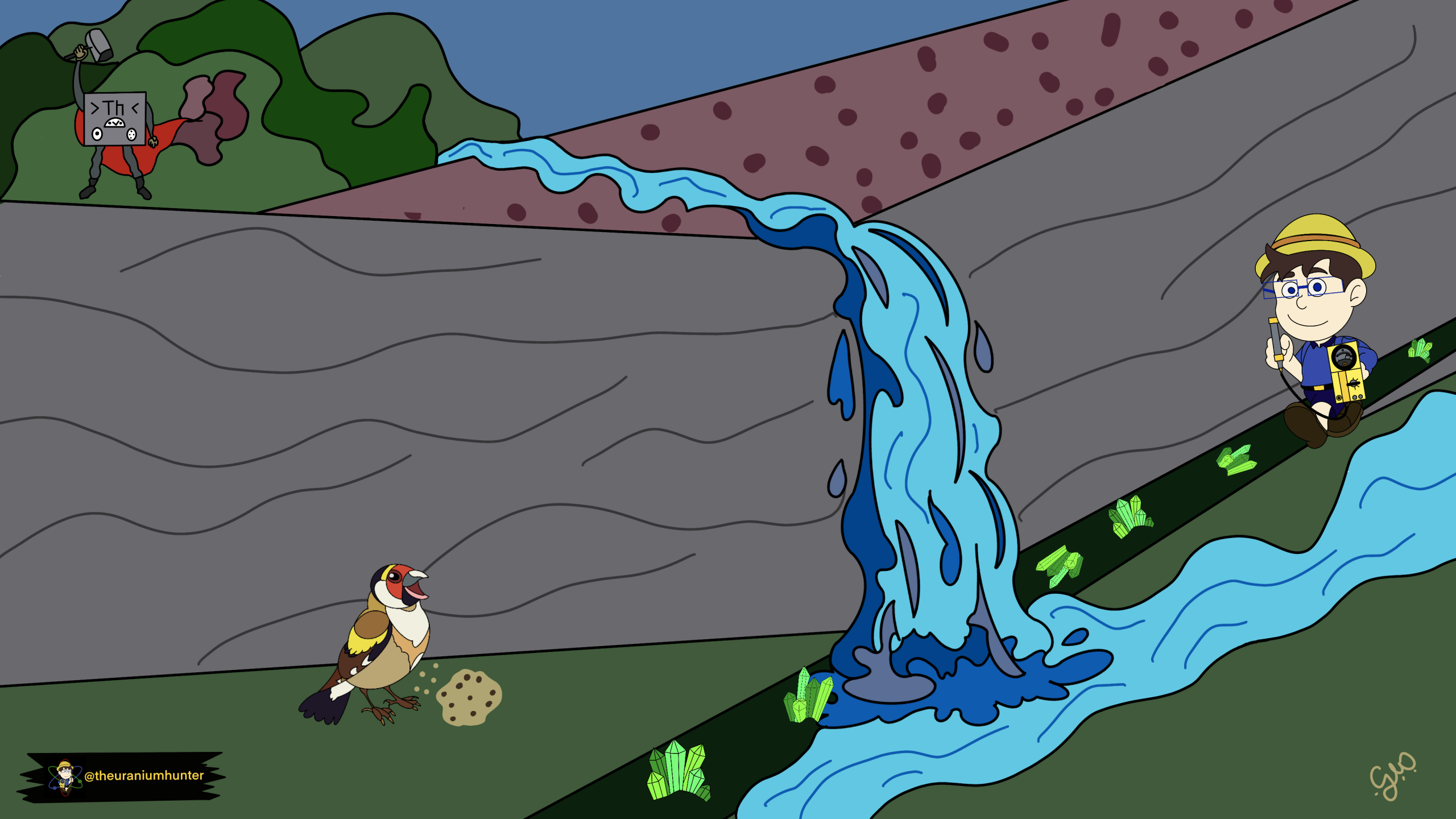

This blog and Part 1 accompany the new YouTube video “Linhope Spout: The Waterfall Hiding Radioactive Secrets – The Three U’s Challenge (Part 1)” – check it out now.

How Haslam’s work demonstrates the mineralisation potential of the Cheviots – and how my own visit confirms it

- Hydrothermal alteration and element enrichment

Haslam’s 1975 surveys showed that the Cheviot granite and its associated structures are heavily hydrothermally altered. The geochemical data revealed consistent enrichment in boron, beryllium, tin and uranium relative to the surrounding volcanic units, indicating that the granite is a source of mineralising fluids. - Poly‑phase mineralisation history

The same surveys documented widespread enrichment of other elements – uranium, copper, zinc, barium, lead, molybdenum, and more – in both drainage samples and rock outcrops. These patterns point to multiple phases of mineralisation driven by successive magmatic pulses from the granite itself and from porphyry intrusions that cut the area. - Field confirmation at Linhope

During my recent visit to Linhope, I located uranium in a dyke that lies close to the granite‑pluton boundary – exactly where Haslam had flagged a minor anomaly in 1975. The uranium was found in situ, within bedrock veins or altered zones, rather than being a surface‑wash or sedimentary enrichment. This direct observation confirms that the geochemical anomalies recorded by Haslam reflect true, hidden mineralisation beneath the soil cover and that these anomalies persist to the present day.

How there has been little research since his 1975 paper despite the interesting conclusions in it

Regional mineral exploration in the Northumberland Trough remained largely “low key” for three decades after Haslam’s 1975 study, with subsequent work limited to Leake and Haslam (1978). A 1988 report, designed to complement the earlier studies, explicitly stated that further work is required to fully clarify the sequence, style, and extent of alteration and mineralisation events in the Cheviot Hills. Thus, the potential highlighted by the early work remained largely unfulfilled for decades, and you are stepping into this research vacuum almost 50 years after the original findings.

What modern tools can reveal next‑generation mineral clues

Haslam’s 1975 work laid the groundwork, but the thick blanket of glacial drift (peat, sand, gravel) in the Cheviots hides the surface clues that geologists normally read from rock outcrops. New, high‑tech methods can pierce that cover and give us a clearer picture.

| What we want to find | Modern technique (plain terms) | Why it helps |

| Hidden uranium‑rich veins | Deeper soil sampling with power augers – a heavy drill that pulls a core of soil straight down through the drift. | It reaches the bedrock that is covered by the drift, showing the true geochemical pattern. In the Cheviots, deeper cores give higher uranium peaks than shallow surface samples, proving the anomalies are real. |

| The granite’s history | Isotope “fingerprinting” of zircon crystals – tiny lab tests that read the exact ages and source of the granite’s magma. | Zircon keeps a perfect record of how the granite formed, something whole‑rock chemistry can’t show. Knowing the granite’s origin refines where we should look for ore. |

| Hidden fault and fracture zones | Airborne radar (or ground‑penetrating radar) and magnetic surveys – drones or planes that fly over the hills and measure the Earth’s magnetic field, while ground‑based radar digs a few metres below the surface. | Faults and cracks often host mineral veins. These surveys can spot those hidden structures even when the ground is covered by drift, guiding the next drill holes. |

| Specific uranium‑bearing dykes | Targeted magnetic and VLF‑EM (Very‑Low‑Frequency Electromagnetic) surveys – handheld or vehicle‑mounted sensors that detect conductive rocks (often rich in uranium). | They help pinpoint the exact fracture zones that Haslam’s anomalies suggest, saving time and money. |

In short, by combining deeper soil cores, isotope dating, airborne radar/magnetic imaging, and VLF‑EM surveys, we can turn Haslam’s surface clues into a clear map of hidden mineral deposits beneath the Cheviot Hills. These tools let us see where the rocks are hiding their secrets, even when the surface is buried under centuries of glacial material.

Why bother looking deeper into the Cheviot Hills? Both a human and a scientific perspective point to a few clear incentives.

1. Hidden mineral treasure – uranium and more

The 1970s geochemical survey showed that streams draining the granite carry on average 10 ppm of uranium, a value comparable to other known granites but higher than volcanic or sedimentary counterparts

Field work at Linhope, where a porphyry dike was found and a heavy‑mineral residue rich in thorium, zirconium and titanium was recovered, confirms that the granite source still holds a “trickle” of radio‑active minerals and that richer veins likely lie upstream, hidden by rugged terrain

If the “Three U’s” challenge is any hint, the hills could hide economically viable uranium or other valuable metals.

2. Untapped scientific record

The Cheviot Hills are the remnants of an ancient volcano that later was intruded by a granite pluton. Hydrothermal fluids once leached heavy metals into cracks, leaving veins that still contain uranium. Studying these processes offers a living laboratory for understanding how deep‑Earth fluids migrate, deposit minerals and evolve over hundreds of millions of years

It also lets us refine models of Caledonian tectonics and the evolution of Proterozoic-Paleozoic terrains – areas that Dr. Haslam’s pioneering work on the O’Neill Group helped illuminate

3. Broader exploration value

Beyond uranium, the granitic environment is richer in beryllium, boron and tin, while volcanic‑draining streams contain copper, lead, zinc and other metals

This diversity suggests the possibility of undiscovered veins of metallic minerals (e.g., copper, zinc, lead) and rare‑earth elements. For prospectors and mining companies, that represents a potential source of resources that could support local economies.

4. Cultural and educational appeal

The Cheviot Hills are iconic English highlands; uncovering their hidden geology would add a new chapter to the region’s natural heritage, offering educational opportunities for schools, universities and the public. The YouTube “Three U’s Challenge” and other media already highlight the intrigue of the hills, drawing interest and encouraging community engagement

Cheviot Gold – A New Hope

In 2000, a large-scale research paper was published: “Exploration methods and new targets for epithermal gold mineralisation in the Devonian rocks of Northern Britain”. It took the research of the 1975, 1978 and 1988 papers to revisit their conclusions, comparing results to similar Cheviot analogues in Scotland. The conclusions were both exciting and tantalising; whilst concentrating on the gold potential in the Cheviots, the combination of a multi-disciplinary approach and the knowledge of the authors A G Gunn and K E Rollin revealed both an appetite for modern exploration of the area, and the wide-range of metals potentially hiding beneath the glacial till.

In short, exploring the Cheviot geology could reveal valuable mineral resources, deepen our understanding of ancient hydrothermal systems and tectonic evolution, and enrich the cultural narrative of a landscape that already captivates scientists and adventurers alike.